Polarization is everywhere, it seems, at the moment. Many seem increasingly attracted to the extremes of debate, leaving little space for voices of compromise. Does this mean we are headed for times of open conflict? Or is there a way to remember our shared humanity, and make it the key factor in framing public conversations? Can goodwill form the bridge that unites opposite sides? Finding workable answers to these questions could be the key to the future of life on our planet.

In this issue, we reflect on how polarization is being expressed in politics, in gender, and in racial and cultural identity, and seek out the positive signs of progress towards a unifying vision. Recognising this vision is especially hard when the voices at the extremes are shouting so loudly. People of goodwill must strive for a point of inner silence from which to survey the passing scene, and place their faith in the unconquerable nature of Good. As Alice Bailey notes, “the heart of humanity is sound”, and the urgency of the times call for creative ways to evoke this good-heartedness in ourselves and others. Fiery compassion for all who are suffering, plus the will to see good work out in the world, are the hallmarks of those who serve at this crucial time. We hope that the ideas contained in this issue can strengthen and support all who seek to work towards a world where goodwill is the keynote of all relationships.

Polarisation – Bridging the Great Divide

One of the significant features of the past one hundred and fifty years or so and in particular of our present few decades is the sense of polarisation that is present in so many different ways within the human family.

This is particularly noticeable within politics because the conflict of ideas and ideologies is not only recognised but welcomed. The various protagonists don’t want to bridge the divides that separate them – they want to win! During the past century, humanity has amassed ample evidence about the effectiveness of the various political ideologies. In their efforts to prove themselves they have mostly all contributed in some measure to human progress; but it has to be admitted that they have also contributed to a good deal of human suffering. So we are now at a situation where the various remedies for social and economic ills, whether of the left, the centre or the right, whether democratic, dictatorial or theocratic, have in general been tried and found wanting. On the one hand imaginative initiatives tend to be drowned in a sea of bureaucracy and dogma; on the other hand the laissez-faire idea of free markets has created a world where those who already have wealth gain more and the underprivileged tend to sink further into a stultifying poverty. In the long run in this world of conflicting ideas, nobody wins, many suffer and incidentally the natural world is hugely impoverished. In addition there is a widespread assumption that one particular ideology or theocracy is the panacea for all human problems and that this has to be imposed upon all for the future good of the world, often at the point of the sword.

People of real goodwill all over the world can now see with clarity that the various ideologies have a tendency to miss the mark and sometimes even to turn utopian dreams into horrifying dystopias. They also see with an equal clarity an urgent need for a new vision of a cooperative spirit in the world of politics.

People of real goodwill all over the world can now see with clarity that the various ideologies have a tendency to miss the mark and sometimes even to turn utopian dreams into horrifying dystopias. They also see with an equal clarity an urgent need for a new vision of a cooperative spirit in the world of politics.

Is it possible that cooperative goodwill is actually not only a realistic pathway to a better future, but perhaps more importantly, that this is probably the only way in which such a future is achievable? This idea leads us to enquire what actually lies at the root of the failure to measure up to their ideals that all the various ideologies seem to demonstrate. Maybe this discovery will point to a technique for progress that will work for everybody.

This is surely summed up in one word – motive. We can state this with certainty; motive is everything. Where the motive is unselfish, for the common good and for lifting society into a better spiritual and material state, however flawed and inadequate the political system, the people operating it will find a way to make it work reasonably well. Conversely, however good and well designed a political system is, if the people operating it are there for the selfish purpose of the accumulation of wealth and power for personality ends, then it will fail. In extreme cases such scenarios can eventually implode into the anarchy and cruelty of a failed state.

Most people would probably assume that the polarisation between left and right is what needs to be bridged. In reality it is the polarisation between what we have at the present and a future world based on the evocation of all that is best in humanity that urgently needs to be bridged. We can distil this into three simple ideas – right human relationships, freedom and the sense of responsibility. For people of a spiritual persuasion this is a human understanding and embodiment of the divine Plan for humanity and the world. So let us first look at what we understand by this Plan, and then we will see what steps need to be taken to move towards it.

We can think of the Plan as an overarching energy of love and goodness that, matrix-like, enfolds our whole planet with the strength that enables all units of life to evolve towards ever more inclusive attitudes of consciousness. As far as humanity is concerned this means a steady working towards an understanding of the soul and a growing ability to anchor its values and attributes in practical day to day living. It is well worth reminding ourselves what these are. Of course, over the centuries they have been summed up in various ways to suit the world’s many cultures and the different states of unfoldment of human consciousness. But for the world in the 21st century we might summarise them as follows: love, a sense of responsibility, identification with the whole, love of truth, selfless sharing, social healing, freedom, modesty in terms of material possessions, joy and even genius.

Straight away we can see where our present situation of national politics, international relations, and economic structures are falling short. They tend to privilege the few at the expense of the many. They usually prioritise national self-interest above the interests of humanity as a whole. At the present time (2018) this characteristic is being unfortunately energised as countries everywhere turn in on themselves. Whole sections of the population in many parts of the world are re-espousing a separative nationalist spirit. This is also reflected in a growing tendency to repudiate the spirit of internationalism that, despite unresolved conflicts and the persistence of personality aims and methods, existed as a powerful ideal for the decades following the 2nd World War. This is a worrying trend that does not inspire confidence for the future.

One of the reasons why internationalism is being rejected by so many is that it is associated in people’s minds with the globalisation of capital and business which arranges its activities around tax avoidance, structural work insecurity and environmental irresponsibility. But perhaps most important of all it is not politically accountable to anyone. People have the sense that they are becoming just expendable pawns in the games of the oligarchs and the mega rich.

However, this is only one side of the picture. There are also countless millions of people in every country who recognise that a sane cooperation based on a realisation of the oneness of humanity is the best way to a good future. They know that a re-commitment to the internationalist ideal not only reflects this oneness, but is also essential to achieving it. They also know that unity is not uniformity. Diversity and multiplicity is the keynote of nature. Perhaps this could serve as a theme as we explore a way forward.

Of course a goodwill newsletter is not competent to produce a political manifesto, nor should it attempt to do so: that is the work of the experts in the political field who have risen above personal ambition and love of power and whose hearts are alive to human need everywhere in the world. But we can and should outline the principles which must underlie the many different experimental approaches.

Participatory Internationalism

Firstly we need a new participatory and accountable internationalism. In the same way that people invest their energies, ideas and visions into their local community, and on a larger scale into their nation, we now need to facilitate this on a wider scale too. The European Union is perhaps humanity’s most recent attempt at this. It is an experiment in process, and no one can predict how its future will unfold. Many whose identification has not yet gone beyond the border of their own country, hope it will fail. Many more are determined to make a success of it. Yet it is supplying humanity with a working prototype of how very individualistic nations can willingly cede some level of sovereignty for the greater good of the whole. To say that this has not been easy is the understatement of the century. Yet it is working. Looked at objectively the development of the sciences, the arts, and the economic life of all the EU countries are one of the major achievements of the last seven decades.

Yet if the difficulties the EU are facing are so challenging, what hope is there for even larger unions? Perhaps we are looking at this in the wrong way. Political and economic union is constrained by things like geography, cultural identity, religious background. On the larger global level, this sort of union is clearly unrealistic at the present time. It would seem that the only possible avenue to approach world unity now must be based on a union of values that will enhance rather than diminish the wide diversity of human experience, tradition and idealism. It will also show how this wealth of diversity is not exclusive and separative; rather it will illumine how all contribute to the health and richness of the greater whole.

The Golden Rule

Fortunately for humanity, these values appear in a strikingly similar form in every culture and religion. They are called the “Golden Rule” – ‘Behave towards others as you would have them behave towards you.’ This only becomes possible when we recognise in our hearts and minds that ‘the other’, wherever they are in the world, is our neighbour. This principle needs to underlie a new science of relationships that will extend all the way from the individual bonds of family and personal friendship right up to the global level. It combines in a simple and beautiful way both freedom and responsibility. It recognises the essential integrity and value of every individual and community in the world, and holds the door open to the reality that all can contribute to the good of the whole and that every part can receive the necessary protection and care from that larger whole too. It is a wonderful exercise to think through what this would mean if, even in only a small way, this principle governed national and international relationships.

The UN

Again, fortunately for humanity, much useful work, experiment, and practical experience along these lines has already been achieved through the activities of the various international bodies for cooperation that humanity has created, in particular the United Nations and its specialised agencies. Being human institutions, they are necessarily flawed – as their detractors are only too keen and quick to point out. Yet flaws can be corrected and better structures developed as the vision of human interdependence becomes more clearly defined. Together they surely point towards a better future for all.

But will humanity have the wisdom and determination to pursue a path along this route? This is the major question of our time. This is where the cultivation of a practical goodwill is so important. Goodwill or innate kindness lies at the heart of every person without exception, though it has to be said that with some, a bit of excavating has to be done to find it! But it can be evoked into practical livingness in the vast majority of people when the vision of human unity and the benefits of a cooperative world order are well and persistently articulated, a task that is in part the responsibility of the media, both traditional and social. This is the way to bridge the polarisations that mar the expression of the better side of human nature and impede its progress along its divinely ordained path of freedom, love and responsibility.

People hold up all the sky

What does it mean to say someone is a man or a woman? This question might seem ridiculous – surely everyone knows, at least in themselves, WHAT they are, since the biological differences are (usually) obvious. Yet for over 2000 years, it has been recognised, first under the name of hermaphroditism, and since the 20th century under the name of intersex, that a small proportion of humans can exhibit traits of both sexes in one body; and in many traditional societies, there are names for people who can be regarded as belonging to a third sex. These facts should make us pause before we claim that masculinity and femininity are fixed and distinct categories. And we may also reflect how, both before puberty, and after mid-life, differences in hormonal make-up can lead individuals of one sex to exhibit some characteristics typical of the other sex – one need only think of the pure high voice of a boy soprano.

So much for the physical factors – what about the psychological and social ones? Is there a sense in which gender is all in the mind – or in the culture? It is widely known that different cultures create and maintain different expectations of the roles males and females should play in society. A significant part of this may arise from the religion that is predominant in that culture – but a Muslim woman in Saudi Arabia has a different range of freedoms from a Muslim woman in Indonesia, so religion is not the whole story.

And what about the thoughts and feelings of each individual? In previous centuries, being born into a male or female body was something that couldn’t be altered, no matter what the person ‘inside’ might want. But since the twentieth century, this is no longer true, and sex-reassignment medical procedures have become increasingly sophisticated. Subjecting oneself to these physical procedures is nevertheless a major step, to say nothing of the mental and emotional hardships that may arise from the opposition of others. So those who do choose this difficult path must surely have a very strong motive for doing so. In their own minds, some essential aspect of their identity must be tied up with the physical sex ‘opposite’ to their original bodies.

Readers might be wondering at this point what these musings on gender and biological sex have to do with the theme of polarisation. The answer lies in the cultural moment that is encapsulated in the emergence of #MeToo and Time’s Up. These fresh expressions of necessary feminist activism focus on the structural problems of sexual abuse, harassment and inequality in the workplace and elsewhere that have been a part of women’s experience, and a source of deep pain, for countless centuries in most parts of the world. They critique both collective behaviour and structures that can be labelled patriarchal, and the actions and attitudes of individual men, under the umbrella term ‘toxic masculinity’. In doing so, some might argue that they are increasing our sense of polarisation within society, by highlighting the differences between women and men, and emphasising grievances and mis-understandings between the sexes.

But this is surely a mis-interpretation, viewing the rising power of the feminine through a distorting lens that sees all human interaction as having only winners and losers, victims and victimisers. It is to return to the hoary old picture of ‘the battle of the sexes’, when a deepened understanding of emerging stresses in relations between the genders should allow us a more nuanced and hopeful view. Some measure of polarisation is needed in order for a new balance to emerge – and this seems to be what is taking place.

Take, for example, the emerging dialogue around consent in sexual relations. This moves on from the broadly understood message of “no means no”, to expect of men that they begin to notice and to respect subtler signals, some of them non-verbal, that women may send in order to show their unwillingness to take things further. Issues such as these, which highlight the masculine relationship to power and to non-verbal communication in relationships, touch upon some of the more subtle structures in consciousness that underpin social and economic inequalities. As such, finding ways to educate men to recognise and respect these non-verbal signals, and then to exercise due restraint, should improve not just individual relations between women and men, but also help to make structural changes in the workplace and daily life.

The issue of consent would perhaps not have surfaced quite so rapidly were it not both for the #MeToo movement (which largely focuses on more unambiguous cases of sexual assault which have previously been swept under the carpet) and for the fact that, according to some US-focused research, women are now doing better than men across a range of economic and educational measures, and may therefore be in the good position to be less tolerant of old patterns of behaviour. The relations between men and women are undergoing dramatic change, and this is affecting both sexes. The writer and broadcaster Hanna Rosin, in her book The End of Men, notes how, at least in certain socioeconomic classes, this is leading to a rise in single motherhood, because women are simply deciding that they no longer need men to provide for them. This is also connected with the decline in manufacturing jobs and the growth of the service economy, which relatively favours the care-giving and relational skills that women have traditionally excelled in. In simple terms, a man’s traditional role as main breadwinner/provider is eroding, which should, in the longer term, lead to a healthy transformation in masculine identity. Examined more deeply, this role of provider functioned in a capitalist economy as a partial substitute for a man’s biological role as protector. So the psychological significance of an erosion of the provider role is likewise more important than it might at first seem. Men are facing an existential crisis in their identity, for if they are no longer needed to provide or protect, then what role can they now step into? This may explain the emergence of groups which focus on re-defining masculinity, such as Rebel Wisdom(1), Promundo(2) and Next Gen Men(3). It is important to affirm that the roles of women and men are changing, allowing them to help each other on the path towards discovering what both femininity and masculinity now mean.

The issue of consent would perhaps not have surfaced quite so rapidly were it not both for the #MeToo movement (which largely focuses on more unambiguous cases of sexual assault which have previously been swept under the carpet) and for the fact that, according to some US-focused research, women are now doing better than men across a range of economic and educational measures, and may therefore be in the good position to be less tolerant of old patterns of behaviour. The relations between men and women are undergoing dramatic change, and this is affecting both sexes. The writer and broadcaster Hanna Rosin, in her book The End of Men, notes how, at least in certain socioeconomic classes, this is leading to a rise in single motherhood, because women are simply deciding that they no longer need men to provide for them. This is also connected with the decline in manufacturing jobs and the growth of the service economy, which relatively favours the care-giving and relational skills that women have traditionally excelled in. In simple terms, a man’s traditional role as main breadwinner/provider is eroding, which should, in the longer term, lead to a healthy transformation in masculine identity. Examined more deeply, this role of provider functioned in a capitalist economy as a partial substitute for a man’s biological role as protector. So the psychological significance of an erosion of the provider role is likewise more important than it might at first seem. Men are facing an existential crisis in their identity, for if they are no longer needed to provide or protect, then what role can they now step into? This may explain the emergence of groups which focus on re-defining masculinity, such as Rebel Wisdom(1), Promundo(2) and Next Gen Men(3). It is important to affirm that the roles of women and men are changing, allowing them to help each other on the path towards discovering what both femininity and masculinity now mean.

Of course, the biological, hormonal differences will not disappear (although pollution by artificial chemicals such as BPA, which mimic the effect of oestrogens, is suspected of affecting these differences); but the psychological and social ground is shifting beneath everyone’s feet. The centuries of trauma which women have endured cries out for healing and transformation. Yet while the crystallisation of the masculine role as the main provider was an unhealthy, even oppressive product of ‘patriarchy’, its dissolution, even if gradual and partial, is also, in a less dramatic way, traumatic for many individual men. In the midst of this, the vast multitudes of men and women are facing up to the need for change. The reality is that the path towards healthy, balanced relations between the sexes is inevitably fraught with difficulty. Women, with their deeper understanding of emotions and relationships, and who have historically suffered most, are perhaps best placed to help heal this trauma.

So the question is, can we, as men and women, find ways to assert the positive characteristics usually associated with each gender, without falling into the trap of repeating stereotypical roles and structures? Take, for example, the idea of aggression – can we find ways to positively channel this energy in society (in its feminine and masculine forms), re-imagining it as the bold, adventurous spirit that seeks dynamic, positive change? We are faced with a number of global crises right now that would benefit from such a spirit, expressed by women and men. Climate change clearly needs not just incremental shifts but bold, even risky measures; the current economic system is evidently not working for the majority, and tinkering around the edges is not enough to produce justice and equality. And the idea of nurturing, which can be stereotyped as passive, is in fact also needed, in terms that see it as sustaining and regenerating our relationships with the other kingdoms of nature, and creatively re-inventing ways to live in community with one another. If it seems that this is just repeating the wisdom of the Tao, that the two poles complement one another to produce harmony – well, there is a reason why such wisdom is called ‘ageless’! When polarisation is perceived as two points of fixed opposition, there is no way forward: but when it is recognised as a fluid dance between the poles, motion and evolution naturally follows.

There is, of course, no purpose in pretending that progress in this area will come easily. For example, the issue of Human Rights concerning gender and sexuality is so controversial that the United Nations has not yet been able to agree upon a formal Declaration (proposals were made in 2008 and 2011). Yet there are signs of hope. A document which could act as a seed for a future Declaration was created by an international gathering of human rights groups which met in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, in November 2006. Updated in 2017, the Yogyakarta principles(4) seek to apply the principles of international human rights law to addressing the abuse of human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people – in other words, all those who do not fit neatly into the traditional stereotypes of gender and sexuality.

Ultimately, do we not all, women, men, and all points in between or beyond, seek to be known for who we truly are and what we can contribute to the wider whole? Do we not seek the free expression of our spiritual core, the soul, through our physical, emotional and mental vehicles, of whatever gender? When we are able to voluntarily shift our sense of identity beyond body, feelings and mind into the soul, we can begin to appreciate that the ‘opposites’ of gender form one synthetic whole, and can direct the boundless energy of spirit into the world in service. Then we can understand ‘male’ and ‘female’ as simply a convenient shorthand for certain constellations of qualities that can be freely drawn upon at will. When this state of being is the general rule, we will be able to extend Mao’s saying “Women hold up half the sky” to the thought, and to the achieved reality, that “People hold up all the sky.”

4. http://yogyakartaprinciples.org

Building Community: Bridging the Divides in Cultural Identity

This is a troubling period for many people of intelligent goodwill. Problems of division and polarization in areas of religion, ethnicity, race and culture can be deeply disturbing for those who recognize the fundamental oneness of life. When this oneness appears to be denied, sometimes in very strong language, by groups from majority and minority communities actively pushing their own cultural and religious agendas, finding a middle way that bridges divides while remaining true to universal values is especially challenging. Addressing issues of concern (education, health care, policing, unemployment etc.) only through the lens of competing racial or religious groups makes it difficult for trust or goodwill or simple respect to flow into relationships. Polarization has a similar effect on the national life to a blocked artery – it interrupts the circulation of the full mix of energies needed for a healthy system.

.jpg) We live in an increasingly interdependent age. While many communities around the world continue to be culturally and religiously relatively homogenous, others are becoming more diverse and mixed. People are moving across borders and around the globe in greater numbers than ever before, and this movement is unlikely to stop. The UN’s Compact on Migration, shortly to be adopted by participating countries after widespread discussion and negotiation, recognizes this and seeks to develop an approach that governments can use as the basis for cooperation and coordination.

We live in an increasingly interdependent age. While many communities around the world continue to be culturally and religiously relatively homogenous, others are becoming more diverse and mixed. People are moving across borders and around the globe in greater numbers than ever before, and this movement is unlikely to stop. The UN’s Compact on Migration, shortly to be adopted by participating countries after widespread discussion and negotiation, recognizes this and seeks to develop an approach that governments can use as the basis for cooperation and coordination.

Right now is a challenging time. Cultures are rubbing up against each other, often at close quarters, during a period of rapid change, and of political and economic uncertainty. Individuals and societies are under significant stress. In most Western countries, secure, stable, fulfilling jobs are becoming harder to find for blue-collar workers. Lives are being disrupted by rapidly changing social mores (e.g. gender and sexual orientation); widespread use of disrespectful language in social media and national conversations; and a loss of trust in religious institutions that had previously helped the large masses of people cope with change. At a time when the desire for bigger, better and more glamorous ‘things’ is constantly stimulated by economies based on competition and growth, overall wages have been stagnant if not declining for most people – while an elite group apparently reap all the financial benefits of increased trade. Quality of life in basic areas like health, education and housing appears for vast majorities to be on a downward spiral. It is not surprising then that, for many regular people, the future seems bleak.

In this situation conflict between cultures within nations (and even within cities and localities) is inevitably heightened. This reflects the transition now well underway, from an age of separation towards an age of synthesis. Transition is a messy affair, involving pain and loss. The suffering should be balanced by a growing a vision of future possibilities. Yet this vision has been over-politicized and expressed in simplistic ‘sound-bites’. If it is to take hold of the popular imagination, this vision of the cooperation that could be achieved now needs to be enunciated with clarity and spiritual fire.

The widely, but not universally, perceived sense of belonging to One Humanity and One Life includes a recognition of the uniqueness of every individual human being; and the rich diversity of cultures, faiths and ways of living – each with their own qualities and challenges. This sense of oneness includes a recognition that a world community is in process of emerging, part of a Great Turning towards an era of interdependence. Before Brexit and the recent rise of popular nationalism, the multi-cultural, pluralistic spirit was considered by many to define the new era that humanity is headed towards. But right now, there is an atmosphere in the public life questioning this openness to diversity and cynically suggesting that it is an ideology spread by cultural elites; nothing more than political or cultural correctness masking the reality of a separateness that is inherent in human nature.

The goodwill vision of co-operation between diverse elements in addressing all the challenges of an interdependent age is now being tested as never before. In the long-term this is surely a good thing. Those who seek to address the source of the problems of racial and religious divisiveness are forced to deepen their understanding and practice of right action; to truly ‘see’ each participant in any local or national dispute (honoring their individuality and group identity and seeking to understand the source of their anger, hurts and fears); to move beyond simplistic slogans and to develop skills of bridging cultural divides in ways that address fear amongst all the communities involved. Recognizing that conflict and polarization exist is the first step in any honest exploration of conflict resolution, bridging into common, universal values of goodness, beauty and truth. Beyond the loud, and sometimes violent, shouting of slogans from all sides of cultural divides, there is a great deal of soul-searching going on. And this is finding expression in strong efforts to understand the fear of the other, and the inherited pain that is embedded in most issues of racial and religious conflict. It is also provoking a widespread reflection on the nature of cultural identity and its role in contributing to a strong, confident national identity, which can then be part of a strong sense of a shared human identity. With this understanding the multi-cultural vision is being re-assessed. This is happening at local, national and global levels throughout the world; just as it is happening through initiatives in law, education, community affairs, and all the professions. There are examples aplenty, including the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project(1) at Northeastern University in Boston, which has become a resource site for efforts within the US promoting dialogue-based opportunities for racial reconciliation; and a UNESCO project(2) being developed through pilot programs in Austria, Zimbabwe, Thailand and Costa Rica, training teachers in developing intercultural dialogue skills amongst their students.

The goodwill vision of co-operation between diverse elements in addressing all the challenges of an interdependent age is now being tested as never before. In the long-term this is surely a good thing. Those who seek to address the source of the problems of racial and religious divisiveness are forced to deepen their understanding and practice of right action; to truly ‘see’ each participant in any local or national dispute (honoring their individuality and group identity and seeking to understand the source of their anger, hurts and fears); to move beyond simplistic slogans and to develop skills of bridging cultural divides in ways that address fear amongst all the communities involved. Recognizing that conflict and polarization exist is the first step in any honest exploration of conflict resolution, bridging into common, universal values of goodness, beauty and truth. Beyond the loud, and sometimes violent, shouting of slogans from all sides of cultural divides, there is a great deal of soul-searching going on. And this is finding expression in strong efforts to understand the fear of the other, and the inherited pain that is embedded in most issues of racial and religious conflict. It is also provoking a widespread reflection on the nature of cultural identity and its role in contributing to a strong, confident national identity, which can then be part of a strong sense of a shared human identity. With this understanding the multi-cultural vision is being re-assessed. This is happening at local, national and global levels throughout the world; just as it is happening through initiatives in law, education, community affairs, and all the professions. There are examples aplenty, including the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project(1) at Northeastern University in Boston, which has become a resource site for efforts within the US promoting dialogue-based opportunities for racial reconciliation; and a UNESCO project(2) being developed through pilot programs in Austria, Zimbabwe, Thailand and Costa Rica, training teachers in developing intercultural dialogue skills amongst their students.

Within this environment one way forward for those who are turned off by the polarized debate between cultural groups is to take responsibility for creating atmospheres of cooperation around common challenges experienced by people of all ethnic and religious groups. This is not to suggest that readers of this Newsletter need to be called to some form of political or community ‘activism’. Some already are involved in this in their own way, but for others ‘taking responsibility for creating the new’ may focus on truly observing what is happening in the world of inter-cultural relations; thinking about the potential for cooperation in their own environment, or whatever field of activity (religion, health, law etc) they are interested in. The goal of this living thinking would be to notice areas where cooperation is blossoming, seeing it in its sometimes flawed human expression (struggling to see through deep-seated glamours and illusions that will take time to be dissipated).

In earlier generations, struggles by Trade Unions, Suffragettes and Civil Rights movements enabled popular forces of goodwill to organize and mobilize, and this led to significant progress in the quality of people’s lives. Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah suggests that today’s identity politics be creatively “re-shaped” so that they might be “more productive” and less oppositional, uniting concerned people in movements experimenting with ways to bridge inequality gaps; to ensure that “no-one is left behind” as the UN is seeking to do; and to fight for better schools, improved access to health care, and increased security in violent neighborhoods. Movements like the climate action group 350.org have the potential to unite people of goodwill from majority and minority communities and these struggles are important as a way for ‘ordinary people’ to become involved in building a better world for all.

In earlier generations, struggles by Trade Unions, Suffragettes and Civil Rights movements enabled popular forces of goodwill to organize and mobilize, and this led to significant progress in the quality of people’s lives. Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah suggests that today’s identity politics be creatively “re-shaped” so that they might be “more productive” and less oppositional, uniting concerned people in movements experimenting with ways to bridge inequality gaps; to ensure that “no-one is left behind” as the UN is seeking to do; and to fight for better schools, improved access to health care, and increased security in violent neighborhoods. Movements like the climate action group 350.org have the potential to unite people of goodwill from majority and minority communities and these struggles are important as a way for ‘ordinary people’ to become involved in building a better world for all.

While an atmosphere of goodwill avoids partisanship, and draws attention away from criticism, it naturally awakens a popular will to create a better world, and a belief in the possibility that better schools or better health care or more fulfilling work can be achieved for majority and minority communities; and that significant progress can be made in the next decade if this is what enough people really want. Those who share this will for the good of all need to be able to debate, discuss and negotiate about how to move forward; and to do so in ways that recognize a common purpose and share a respect for differences.

Perhaps the most important and positive item to report about bridging the divides in cultural identity is that there are more transformative initiatives creating spaces for soul-searching, dialogue and action in this area than at any other time in history. They just don’t hit the headlines. But an online search will reveal countless well established and influential initiatives in inter-racial and inter-faith conflict resolution working at local, national, regional and global levels. These include the Conflict Transformation Strategies(3) and Racial Healing Resources(4) with a tool-kit of tried and proven practices for schools and communities to engage opposing groups in dialogue that moves beyond conflict and into understanding, often leading to shared action. The NGO Search for Common Ground(5) has developed numerous programs around the world using such practices as Active listening, ensuring that others will feel heard and acknowledged; Seeking to understand others’ underlying interests beyond their stated positions; Avoiding assumptions when possible, and checking assumptions when they are present. At an international level the United Nations Alliance of Civilizations(6) has well-established programs focused on intercultural dialogue, understanding and cooperation. In 2017 the Commonwealth Secretariat established a Unit(7) to support national strategies to counter violent extremism amongst the 53-member states of the Commonwealth. These shine a further light on the multitude of initiatives designed to foster in-depth approaches to the work of bridging divides across cultures, so that there can be cooperation for the common good.

2. https://en.unesco.org/news/building-intercultural-skills-austria

3. https://racialequitytools.org/act/strategies/conflict-transformation

4. http://racialequitytools.org/act/strategies#ACT18

5. https://www.sfcg.org/what-exactly-is-the-conflict-around-race/

7. http://thecommonwealth.org/countering-violent-extremism

Image Credits:

Top banner Kim Paulin, https://www.flickr.com/photos/axlape/1463432010/in/album-72157602209067430/ (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence)

In "People Hold Up Half the Sky" Polarities: Yin and Yang ©Millicent Hodson

In "Building Community: Bridging the Divides in Cultural Identity" Marco Verch, https://www.flickr.com/photos/30478819@N08/21464593154/in/album-72157659643913076/ (CC BY 2.0 licence); and Shutterstock, ValeStock, www.shutterstock.com

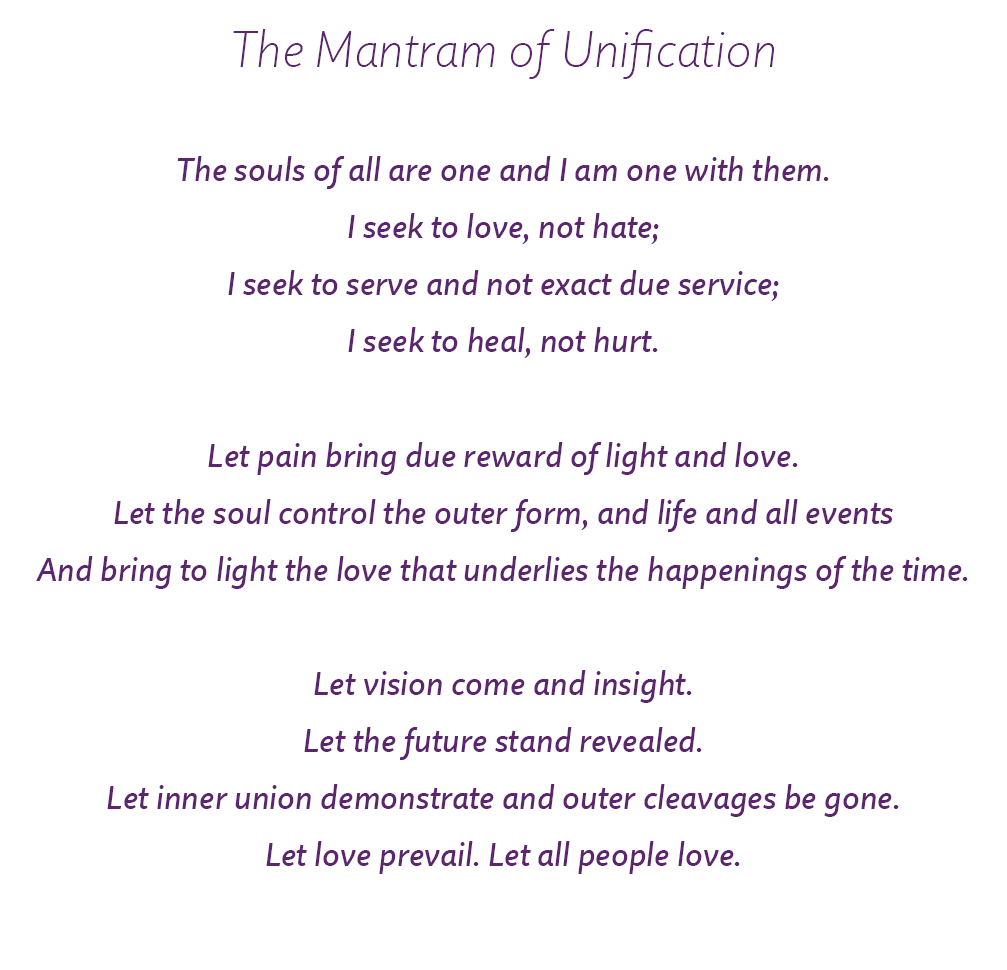

In "The Mantram of Unification" Shutterstock, Hibiki Nakata, www.shutterstock.com