WATCH ON YOUTUBE

Craig Holdrege

(Director, Nature Institute)

Today we will look at our relation to the natural world and how, through a certain way of studying and contemplating nature, we can ourselves become more alive. There is an immense force of spirit in the world everywhere, and in the living world in particular. But we human beings are in our minds so often separate from the source of things. We can, through interaction with the living world, touch that source and recognize not only something of the life of the world but also come to a greater cultivation of the life within ourselves.

To begin with let us look at a symptom of a problem that many of us have as modern human beings. Water is something incredibly dynamic, beautiful, powerful, and also gentle. We all need water to live. And it’s very interesting what happens when we begin to study water in a conventional scientific way. Water changes dramatically—it becomes an assemblage of molecules that interact. We start with something fluid and connected and dynamic, and make it in our minds into something that is made up of many different separate parts. And that is a habit of thought we have everywhere—we do this when we talk about genes, we do this when we talk about the basis of matter and picture separate atoms. Our modern mind has a tendency to think that the world consists of separate entities that interact. And you can see this thread throughout much of modern science, which has so dominated our culture for the last 400 years or so. We imagine separate building blocks that make up the world. We build up out of separateness and if there are connections, the connections come because separate things are interacting. Separate atoms interact to make molecules, and molecules combine to make a substance like water, and genes combine to make an organism. It is as though we have taken as the exemplar for the reality of the world objects that are to a degree separate, like stones or chairs—what we call things. It seems to me that this is very powerful and suggestive, and one can do a lot with this way of viewing the world. But it is also hugely limited.

Now let’s look more carefully at living organisms. Plants start as seeds, in one sense as isolated things. But if the seed remains isolated it will over time die and disintegrate. The moment the seed begins to germinate, it develops by overcoming separation at every moment. As the root begins to emerge out of the seed, it “knows” where to go, namely downwards. A tap root grows towards the center of the Earth, as all tap roots do everywhere on the earth. If you think of the planet as a whole, all the tap roots everywhere are all pointing towards the center. They all have

this orientation and all plants are connected with the whole of the Earth. And then plants unfold in the other direction—into the air and into the light, taking up immediate connection with this world, which allows life to happen. The plant orients toward the sunlight in its leaves, takes in the light and also air, and through the roots water and a small amount of minerals. In this way (we speak of photosynthesis) the plant creates more living substance and grows.

A plant, as an example of a living being, is always living in connection and not in separateness. So the question is, how can we learn to think about the world and sense the world more in relation to connectedness, to unity. One way is to carefully study the plant and by interacting with these remarkable beings who allow us to live on Earth by creating oxygen and living substance that sustains us. We can try to learn from plants about their way of being, and by learning from them we learn something also about ourselves and life in the world.

There is never a moment of life that isn’t accompanied by something dying as well. The development of the plant means producing something new (leaves, buds, flowers, etc.) but also letting something else fall away, such as older leaves. Plants go through a process of transformation. Everywhere you look there is transformation, and for a plant it means unfolding itself out into the world, creating new parts, then shedding what is no longer needed, and moving on to a new stage. The interwoven nature of life and death is a very beautiful and intricate process.

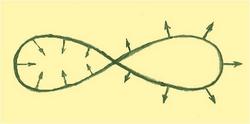

So when we study these kind of phenomena in the world with plants, we can also ask: How we would think if were to think in the way a plant grows? We would begin to move from separateness and move beyond combinatorial thinking, in which we put together separate thoughts. Of course this kind of thinking is necessary for everyday navigation in the world. But now attend to the activity of developing a “train” of thought, or to put it more vitally, developing a plant of thought. What would that look like? This might entail going out into the world with a heightened attention; you would carefully take in what is around you, so you become rooted in things. And then in this rooted perception of things you begin to develop an idea about another person, about a problem, about a task to do at work. And then based on that experience you bring forth another leaf, another idea and then another. We come into a flow and, as in the plant there is continuity but also new experience and learning.

What we human beings often do is to fall in love with our ideas and say—“this is right.” We don’t want to let them go. But a plant “knows” better. Even though it grows beautiful leaves and beautiful flowers and branches, if it is going to continue to develop it has to let things fall away. Only in that way can something new emerge. We always have to be willing to let go of what we cherish at any given moment. That is one aspect of thinking like a plant. And we can make this a practice when we catch ourselves falling in love—in the negative sense of falling in love, that is, in becoming enamoured—with an idea, thought or opinion. Then we have to step back and say, wait a minute, treat that idea like a leaf. It’s good something has manifested but what else wants to develop out of the process? We needn’t think that our insight or opinion is the be-all and end-all. We have to stay in process. And it’s very interesting to ponder what a flower of thought is, what a fruit of thought is and what a seed of thought is.

Plants can in this way become teachers of transformation, transformation meaning growth and letting go, staying in movement and being

dynamic. Plants can also become teachers of context sensitivity. Every plant grows in intimate interaction with its environment and also reflects the different qualities of that environment, as the six different specimens of wild radish show. The tiny plant on the left grew in disturbedand compacted soil, while the plant on the right grew in a meadow.

When we are context sensitive in our attitude toward the world then we have a sense of our being-in-the-world. We perceive the context, and think and act in close relation with it. It’s not a matter of “I’ve changed the world” but “I’ve been changed by the world and I also change the world.” Something new comes about that didn’t exist before—a dialogue, if you will, between connected beings.

A process of inner transformation can go on within a human being as a result of interaction with the world. We often think of meditative practices in which we set ourselves apart from the world. But science and inquiry can become a field of meditative practice. When, for example, we really want to enter into the dynamic of the plant’s life, we have to move beyond observation. Observation morphs into a spiritual practice when we use visualization to recreate the image of the plant or the animal in our mind’s eye. We can do this purposefully by trying to inwardly recreate what we’ve perceived. So if we’ve been observing a plant once a week for a few weeks, before we go out the next time to observe we can inwardly picture what the plant looked like the week before. We then see what the plant actually looks like today. And then we can compare the two pictures in our mind and experience more deeply and consciously the process of transformation. This is an inner practice, a practice which the poet and scientist Goethe called exact sensorial imagination. In a precise way, based on sensory experience, we can mobilise the forces of our imagination to participate in the living process within ourselves. The life of the world begins to show itself more clearly.

An ecologist has written, “How does one speak about connection in a culture of separation and isolation? I do not know." This is a very honest statement from a primer on ecology. Ecology is about connection, but this ecologist rightly wonders how we can speak about connection in this fragmented world. This is a boundary that we in science need to move beyond. And if we observe plants in the right way it can help us to do just that. David Bohm said, “The whole ecological problem is due to thought. Because we have the thought that the world is there for us to exploit and so no matter what we do pollution will all get dissolved away. Thought produces results but thought says, ‘I didn’t do it.’” So we are self-forgetful. If the plant is to become a teacher of living connectedness, it can only do so if we are also paying attention to thought, if we are self-aware in that process so that we can then home in on the process of living thinking.

In conclusion, here are a few words from Goethe, “As human beings we know ourselves only so far as we know the world. We perceive the world only in ourselves and ourselves only in the world. Every new object, clearly seen, opens up a new organ of perception in us.”

[The images are from Craig Holdrege’s recent book, Thinking Like a Plant: A Living Science for Life (Lindisfarne Books, 2013)]